Most Lakes and Streams Meet Water Quality Standards

Urban Waters More Likely to Have Poor Water Quality

WHY IT MATTERS

The Casco Bay watershed includes all lands and waters that drain to Casco Bay. The watershed is linked hydrologically and ecologically, from headwaters to the Bay. Flowing waters transport wood, sediment, and other materials downstream, carving the valleys and shaping the stream channels that provide habitat for aquatic organisms. If rivers and streams are healthy (and unblocked by dams or other barriers) they allow fish, aquatic insects, and other animals to move from bay to river to lake and back again.

If water quality is poor, however, not only can pollutants be transported downstream to the Bay, but those long-distance ecological linkages can be disrupted, lessening the ecological integrity of our waters, including the Bay. Both direct and indirect effects of poor water quality in the watershed make our lakes, rivers, and the Bay more vulnerable to other stressors, including climate change.

The fresh waters of the Casco Bay watershed are a major economic asset. Our lakes, rivers and streams support boating and recreational fisheries. Our region’s healthy waters underpin a robust tourism economy. Sebago Lake provides drinking water to more than 200,000 people in Portland and the surrounding region.

STATUS

Lakes, Rivers, and Streams

Under Maine law, every body of water must meet water quality criteria, specific to the “designated uses” associated with the waterbody’s assigned water quality class. For example, lakes, rivers, and streams must have sufficient dissolved oxygen to support healthy insect and fish communities. Waters that do not meet related standards are labelled as “impaired”.

Biomonitoring

The Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has developed statistical tools to evaluate the health of rivers and streams based on the composition of stream biota, especially invertebrates like insects, snails and worms. DEP uses invertebrate data to determine whether a stream meets Class A (best), B, or C requirements, or is in “non-attainment” (not meeting even Class C standards). We looked at the most recent biomonitoring results available from sites monitored over a ten-year period (2009 through 2018).

Percent Impervious Surfaces in Watershed

Biomonitoring shows that streams in urban areas (darker gray on map) have less complex communities of insects. Streams with healthy insect communities are most likely to be found in rural areas with lower amounts of impervious surfaces (lighter gray).

| Observed Class | Mean | Standard Error | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5.2 | 1.28 | 15 |

| B | 9.9 | 2.96 | 9 |

| C | 13.0 | 3.52 | 4 |

| Non-Attaining | 26.9 | 2.89 | 27 |

| Indeterminate | 8.5 | 1.11 | 13 |

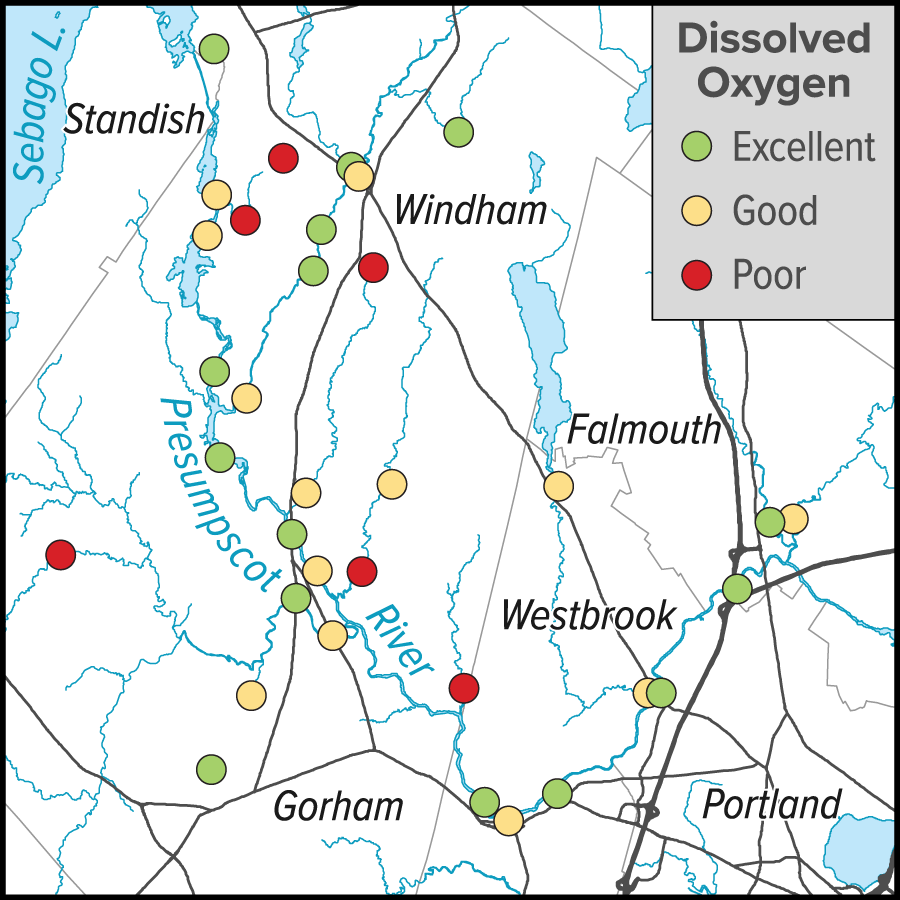

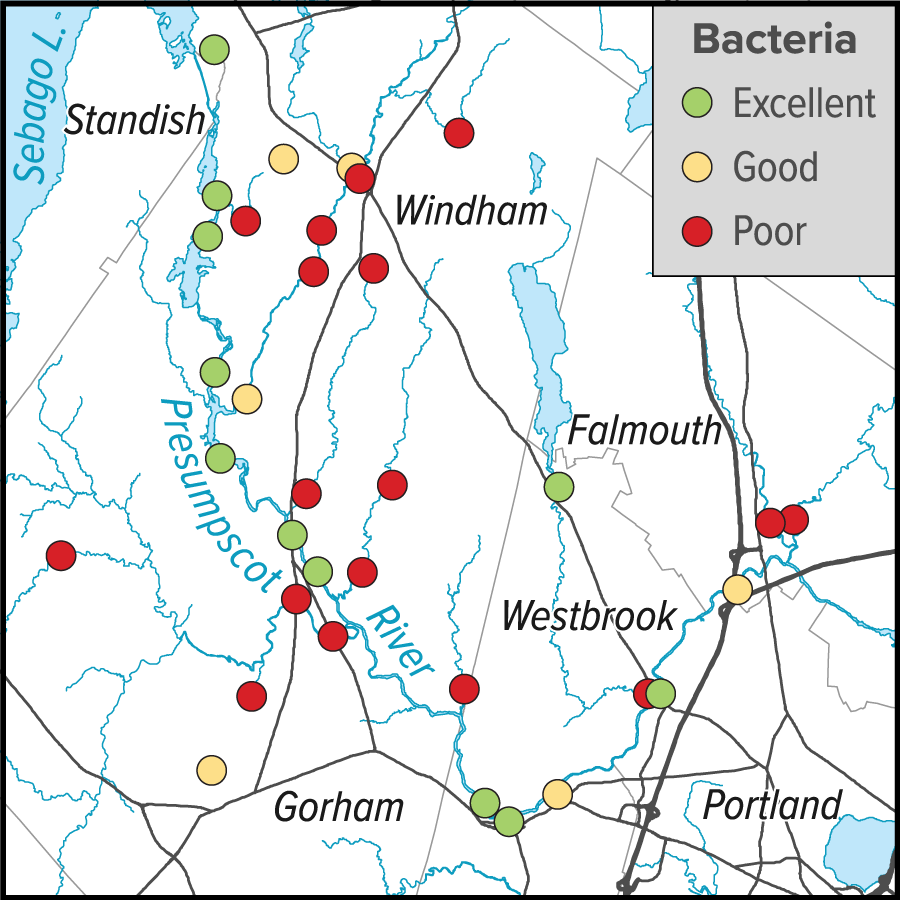

Presumpscot Region River Monitoring

A dedicated group of volunteers, led by Presumpscot Regional Land Trust (PRLT), monitors water quality in the Presumpscot River and its tributaries. Data on dissolved oxygen and bacteria levels were collected regularly from over thirty sites from 2015 to 2019.

The PRLT data shows that instances of poor levels of dissolved oxygen (first map) are uncommon, but elevated bacteria levels (second map) are widespread. When compared to State water quality criteria, conditions at most sites along the main stem of the Presumpscot and Pleasant Rivers usually have acceptable levels of dissolved oxygen and meet bacteria criteria. Several tributaries have persistent problems with low dissolved oxygen, and most show elevated levels of E. coli bacteria. Elevated bacteria levels pose a potential health risk, especially to swimmers. (Excellent: Meets class A/B standards almost always. Good: Meets Class C standards almost always).

Lakes and Ponds

Maine has a long history of monitoring lake water quality, with data for some lakes extending more than 40 years. Much of the data has been collected by volunteers working with lake associations or regional monitoring networks. DEP aggregates and curates lake data, releasing it to the public. (Data on recent conditions in Sebago Lake were provided directly by Portland Water District.)

Monitoring practices vary from lake to lake, and have changed over time, so not all water quality indicators are available for all lakes, or for long enough to evaluate trends. Most monitoring programs, however, have long collected Secchi depth data. Secchi depth measures relative water clarity based on how deep an observer can see a dinner plate-sized disk—the greater the Secchi depth, the more transparent the water. Tens of thousands of observations have been collected from waterbodies in the region. The length of the record varies for each lake, with only a few recent samples for Duck and Bog Ponds, and thousands collected over decades from our most heavily studied lakes.

Table: Water clarity in most lakes in our region has been stable or improving slowly. Secchi depths in more than half the lakes in our region have improved over the past ten years. Longer-term (more than fifteen years) conditions have improved in just under half. Only five lakes show evidence of declining water clarity.

| Water Quality Trend | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lake | Short Term (<10 Year) | Long Term (>15 Year) |

| Adams Pond | Improving | No Change |

| Bay of Naples Lake | No Change | No Change |

| Bear Pond | Improving | No Change |

| Bog Pond | No Change | No Data |

| Coffee Pond | No Change | Improving |

| Cold Rain Pond | No Change | No Change |

| Collins Pond | Improving | No Change |

| Crescent Lake | No Change | No Change |

| Crystal Lake | Improving | Improving |

| Crystal Lake | Improving | No Change |

| Duck Pond | No Change | No Data |

| Forest Lake | No Change | Improving |

| Foster Pond | Declining | No Change |

| Highland (Duck) Lake | Improving | Declining |

| Highland Lake | Improving | Improving |

| Holt Pond | No Change | No Change |

| Island Pond | Improving | No Change |

| Keoka Lake | Improving | Improving |

| Little Moose Pond | No Change | No Change |

| Little Sebago Lake | Improving | Improving |

| Long Lake | Improving | Improving |

| Long Pond | Improving | Improving |

| Notched Pond | Improving | Improving |

| Otter Pond | No Change | Improving |

| Panther Pond | Improving | No Change |

| Papoose Pond | No Change | Improving |

| Parker Pond | Declining | No Change |

| Peabody Pond | Improving | No Change |

| Pleasant Lake | Improving | No Change |

| Raymond Pond | No Change | Declining |

| Sabbathday Lake | Improving | Improving |

| Sebago Lake | Improving | No Change |

| Songo Pond | Improving | Improving |

| Stearns Pond | Improving | Improving |

| Thomas Pond | Improving | Improving |

| Tricky Pond | No Change | Declining |

| Woods Pond | Improving | Improving |

westbrook projects reduce dischargeS to presumpscot river

Portland Water District (PWD) provides drinking water to over 200,000 people in the Portland region. Sebago Lake’s excellent water quality requires less treatment than other lakes, which reduces the cost of distributing safe drinking water to PWD’s customers. If Sebago Lake’s water quality were degraded, PWD would have to invest tens of millions of dollars in additional treatment facilities, causing higher water rates.

Like other drinking water providers that rely on surface water, PWD works to protect water quality by addressing upstream threats. But the Sebago Lake watershed is about 440 square miles in area. Thus PWD partners with many other organizations (including Casco Bay Estuary Partnership) to combine watershed protection efforts.

If each subwatershed above Sebago Lake is protected, then Sebago Lake itself is likely to remain healthy. One way to prioritize watershed protection, therefore, is to look at each lake in the region and prioritize projects that can benefit lakes that are most vulnerable. But how do we know which lakes are most vulnerable?

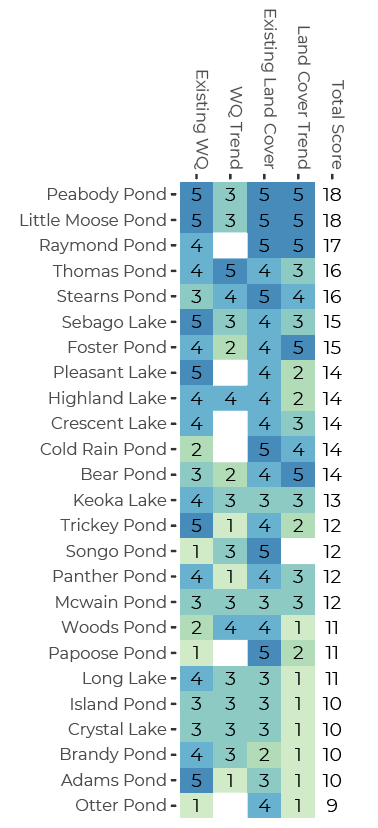

Several years ago, PWD (working with University of Southern Maine, the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, and the Cumberland County Soil and Water Conservation District) developed an index of lake condition and vulnerability. The index is based on evaluation of water quality and land use, considering both existing conditions and long-term trends.

PWD’s Lake Index shows clearly that conditions for some lakes are more concerning than for others. Each lake is ranked from 1 (worst) to 5 (best) in each of four categories, with 20 being the highest overall score or index. (Blanks show where indexes could not be calculated because of insufficient data; assumed equal to 3 for calculating totals). The eight lakes with the lowest index are seeing rapid conversion of forests, which help protect water quality, to other land uses.

successes & challenges

- Our region has a large, diverse constituency for clean water, which supports efforts by organizations and state agencies to protect water quality. Lakes are safeguarded by lake or watershed associations and regional lake organizations. Boaters, anglers, hunters, hikers, and residents recognize the importance of our lakes, rivers, and streams. Businesses from tackle shops to hotels and real estate agencies benefit from clean water.

- All of Maine’s fresh waters are polluted by trace levels of mercury, principally transported from coal-fired power plants in the Midwest. A national transition away from fossil fuels as our economy’s primary energy source would not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but also mercury pollution in Maine.

- Forests and wetlands protect water quality. Close to two-thirds of the Casco Bay watershed remains forested, and the proportion of forested area inland is even higher. Water quality in many of our inland waters remains excellent.

- Replacement of forest with suburban and urban land degrades water quality. Thus expansion of Portland’s suburban and exurban communities threatens water quality in our lakes and streams. That is true even if local communities follow regulations and policies designed to reduce the impact of suburbanization. Investing in forest conservation can help safeguard water quality for future generations.

- Natural wetlands and floodplains reduce flooding, protect water quality, and support stream ecosystems. Native floodplain trees and shrubs shade streams, cool the water and ensure a healthy supply of dissolved oxygen. They slow flood waters, protect the structural integrity of stream channels, and build stream habitat. Floodplain vegetation supports aquatic food webs by contributing food for aquatic insects, and also protects habitat for the terrestrial adult forms of many aquatic insects.

View a PDF version of this page that can be downloaded and printed.

View references, further reading, and a summary of methods and data sources.

STATE OF CASCO BAY

Drivers & Stressors

What’s Affecting the Bay?

Human Connections

What’s Being Done?

If you would like to receive a printed State of Casco Bay report, send an email request to cbep@maine.edu.

This document has been funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under Cooperative Agreements #CE00A00348-0 and #CE00A00662-0 with the University of Southern Maine.

Suggested citation: Casco Bay Estuary Partnership. State of Casco Bay, 6th Edition (2021).